links for 2008-11-28

-

Doctorow interviewed on his book 'Little Brother': "I'm a presentist," he says, smiling broadly as he leans back in his chair. "All science fiction writers, whether they admit it or not, are writing metaphorically about the present. To extrapolate the future is really to comment on the now." Marvelous.

-

"Speculation about the future of the national mapping agency – holder of one of the government's most valuable collections of digital data – arose in the run-up to Monday's pre-Budget report. The Sunday Times suggested Ordnance Survey was one of several state-owned businesses that would be privatised to help the chancellor balance the nation's red ink-filled books. But it was wrong."

links for 2008-11-27

-

Nova highlights Bleeker's participation in the IFTF 'Blended Realities' programme, incl. pics.

-

"KashKlash is a space to share thoughts on, and to shape, the future; a playground for visionary people like you, who, in a sense, are already living a few years ahead. Let’s start from the basic consideration that people have always shared and exchanged things. Sure, it comes to us naturally. But today’s digital communication systems are changing and expanding this age-old behaviour: not only are there new things to share – pictures, music, ratings, writings, videos, data and information – but there are now also many more platforms and opportunities for sharing and exchanging to take place."

-

Nova reports: "The first issue of Design Research Quarterly features the above map that represents the “topography of design research” (made by Liz Sanders). She basically mapped the different approaches to design research based on two dimensions: 1. Their impetus: tools and methods coming from design practice versus those coming from the research perspective. To date, as she points out, most of the methods seem to be coming from the research field. 2. The mindset of those who practice and teach design research: the expert versus the participatory mindset. Which actually corresponds to the level of engagement designers have with people (informants, users, etc.)"

-

Ito reports on the findings of the Digital Youth Project: "It's been over three years in the making, but we are at long last releasing the results of our Digital Youth Project. The goal of this work was to gain an understanding of youth new media practice in the U.S. by engaging in ethnographic research across a diverse range of youth populations, sites, and activities. A collaboration between 28 researchers and research collaborators, this was a large ethnographic project funded by the MacArthur Foundation as part of their Digital Media and Learning initiative"

-

Doctorow: "Here's Far Cry 2 technical director Dominic Guay talking about the importance of "procedural content generation" for massive online games — basically, using software to create worlds that had previously been hand-built by artists. It makes a lot of sense, but what fascinates me is the narrative possibilities for fiction about games: these procedural systems have or will shortly attain a level of complexity that makes it impossible to predict their outcomes. It's the Halting Problem — worlds where software off the rails could generate impossible situations, upside-down worlds, treasure heaps, cowardly monsters and brave grass"

-

"New analysis from Frost & Sullivan, Exploring the European Union Research Policy in Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing, details key disappearing computer projects launched under the EU Fifth Framework Programme, during the period 1998-2003, including 2WEAR, ACCORD, FEEL, Interliving, GROCER, Ambient Agoras and E-Gadgets, among others."

-

Nova highlights how the 'uncanny' is a perhaps overlooked and important aspect of design. Uncanny here means "the familiar can act strangely", in this example it is related to robotics but it could of course relate to anything with a degree of automation. I think Serendipity is probably important too… you cannot design 'for' the uncanny, simply pay attention when it happens.

-

If you use OS maps to gather data for public use: "According to Ordnance Survey, the government's mapping agency, you've just broken its copyright, because the map you checked is licensed from it. And your […] licence, like most OS licences, doesn't allow you to put data derived from an OS map on to the world-visible Google Maps – even though Google's maps are also licensed from OS."

Productive reductive computing

Towards the end of a recent meeting with my supervisors I was asked a question that went something along the lines of: “do you buy the argument that if something is computational, that it is then necessarily reductive?” An excellent question I think. I suggested at the time, and still believe, there are two answers to this question that go together. First, by virtue of what computing ‘is’, as a machine-enabled set of processes that rely by and large on languages based in a formal logic, we must answer ‘yes’. Second, ‘computing’ as an activity and ‘computers’ as devices do not exist in a vacuum they are a part of our lives. I am writing a blog post using my laptop, connected to a network of other computers, run and maintained by people, allowing me to ‘publish’ my thoughts on a web site held on yet another computer, and hopefully some other people are reading this! Therefore, computing is definitely a part of the ‘politics of things‘, as suggested by Latour, with and by which we and others socialise.

My two answers are not mutually exclusive, “either/or”, they go together such that, I argue, we must increasingly see ‘computing’ as a connective capacity. Computing connects people with other people, people with ideas, information with things, etc etc. In this way, I have some sympathy for those, like Adam Greenfield, that suggest that “ubiquitous computing”, or something like it, was somewhat inevitable. However, I think hindsight definitely smoothes out the errors and stumblings along the way. If we think about ubiquitous computing as “the application of computational tools to human activity regardless of the shape and form of those tools”, following Scott Carter (whom I interviewed this summer), I think we can see computing as an ‘affordance’, the capacity to enable possible actions, which is innately connective. Here we might start looking to Gregory Bateson or Deleuze and Guattari to theorise such a connective capacity.

Why do I blog this? It is useful to keep probing concepts central to, and perhaps assumed, in one’s arguments, and I don’t want to lose sight of the fact that the idea of ‘computing’ is not neccesarily fixed.

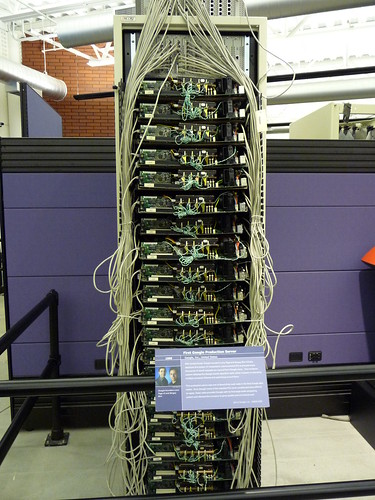

Image: Google’s first server, held in the Computer History Museum, CA, taken by me.

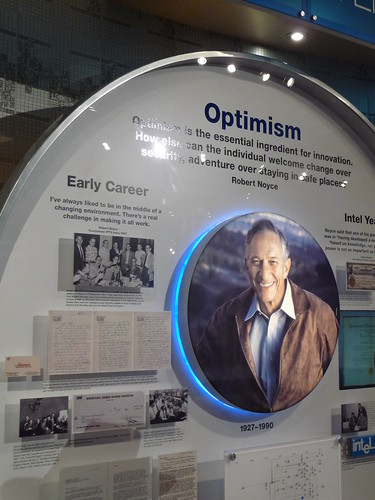

Intel’s “Optimism”

The central quote, by Robert Noyce, from this exhibit at the Intel museum is: “Optimism is the central ingredient for innovation. How else can the individual welcome change over security, adventure over staying in safe places”.

The ‘tomorrow’ of 1991

Image taken from Tacita Dean – Disappearance at Sea

In September 1991 Scientific American had a special issue focussing on ‘Communications, Computers and Networks’. An impressive array of articles were collected in this issue, including Mark Weiser’s ‘The Computer for the 21st Century‘, which is often referred to as the foundational article for ‘Ubiquitous Computing‘. An article later in the issue, simply entitled ‘Networks’ by Vint Cerf, expertly charted the issues that were to arise in the exponential growth of the internet. Also in the special issue was an article by Alan Kay about ‘Computers, Networks and Education’, expounding the ideals he set forth in his proposal of the ‘dynabook‘ to think about how technologies can be allies not hindrances in education. In the introduction to this special issue of Scientific American, Michael L. Dertouzos suggests that:

“the authors in this issue share a hopeful vision of a future built on information infrastructure that will enrich our lives by reliving us of mundane tasks, by improving the ways we live, learn and work and by unlocking new personal and social freedoms”.

links for 2008-11-22

-

Marvelous cartoon biography of Alan Kay's vision of the dynabook, the first notion of a 'portable' personal computer. Alan Kay was the Xerox PARC chap that said 'Look, the best way to predict the future is to invent it'.

Alan Kay’s cartoon journey to the laptop

Joseph Lambert has created, for Business Week, a marvelous cartoon, following Steve Hamm’s new book, charting Alan Kay’s significant role in the development of the personal computer and, in particular, the development path of the laptop. To quote John Markoff’s excellent book, What the Dormouse Said:

Kay’s ideas frequently brought him into conflict with Xerox’s management. He had little patience for the company’s top strategic planner, Don Pendery. To Kay, Pendery saw the world in terms of “trends” and thought defensively, asking, “What was the future going to be like and how can Xerox defend against it?” This drove Kay to distraction, until one day he got so angry he blurted out [the now infamous], “Look, the best way to predict the future is to invent it.”

Marvelous!

I guess there are two ways of looking at the form of invention Kay suggests. The first is cynical – futures can be controlled and explicitly directed for profit. The second, and I think Kay’s intended meaning, is that researchers have a responsibility to experiment with, and propose, what is not yet possible. As Ryan Aipperspach once insightfully said to me: “as a researcher or designer there is an interesting responsibility to design and propose things that aren’t completely possible.” This is perhaps exemplified by Lars Erik Holmquist’s ideas about prototyping, or Mike Kuniavsky and Liz Goodman’s “Sketching in Hardware” conference.

links for 2008-11-19

-

"The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, stated simply, holds that the act of observing an electron perturbs it so that its position and momentum cannot be measured simultaneously. A modest logical extrapolation might engender a Media Uncertainty Principle: when the mass media cover science, any given result is inevitably highlighted simply by reporting it, in a way that affects, positively and negatively, the public perception of science and the evolution of science itself."

-

Nova highlights a location-based game modeled on the idea of 'turf wars'.

-

"there are still a disquieting number of contemporary voices suggesting that all is not well with science journalism. "Science in the daily media is too often reported in the same deferential way as political journalists used to report politics in the 1950s," says Jonathan Leake, science and environment editor at the Sunday Times. "Many of the tensions, rows and skulduggery in the science community get far less attention than they would in business or politics.""

links for 2008-11-18

-

Proof positive that Britain played a big part in the development of the modern computer.